Part of the Looking for Common Ground series

Lisa Johnson for Upstream

A fourth-generation farmer is caught between life and legacy as he ponders the end of an era

On the day spring farm work began in Grant County, Minnesota this year, for the first time in over 100 years, Martin Johnson’s descendants weren’t heading for the fields. Actually, they were headed for Spain.

Jay Johnson may be the last of Martin’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren who have lived and worked on around 1200 acres in Grant County since Martin and his wife Sophy settled here in 1892.

Jay grew up farming with his father and grandfather beginning in the 1960s but now, he may be the last Minnesota farmer of the line. Heading out of Grant County (much less the country) during what his grandfather called “the busy time” would have been unheard of in previous generations. But Jay is a farmer with a foot in two worlds. He and his wife, Betty, live on the home place outside of Elbow Lake where Jay was born and raised and where they raised their own family. But they also have a condo in the Cities, a home base from which to enjoy family, friends, and all the culture a big city can provide. Jay is a musician and world traveler (who’d been known to leave the fields early to attend a rehearsal or perform) with a legacy of family farming on the same land his people have lived for generations. And as he and his wife contemplate retirement, what to do next isn’t just a matter of lake cabins or Arizona in the winter: it’s a complicated mixture of legacy, responsibility, tradition, respect for and loyalty to previous generations, defining what constitutes “home,” and figuring out where you really want to be.

The Beginning

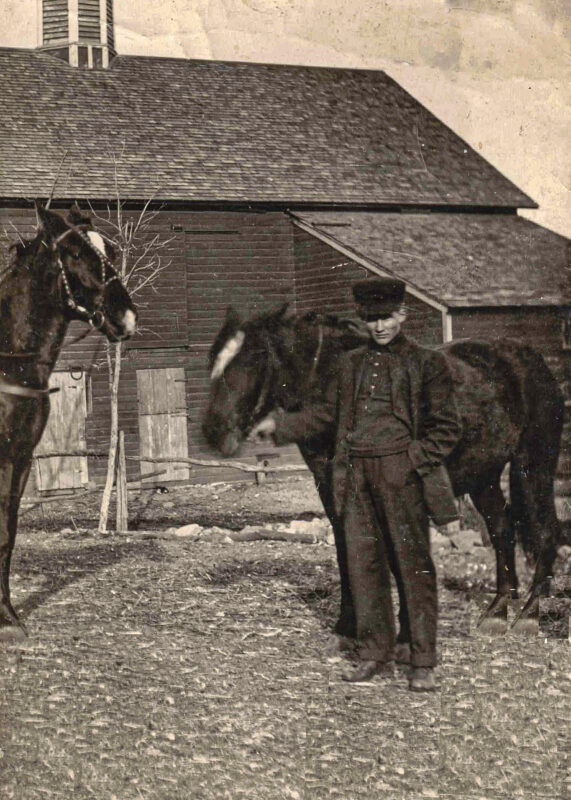

Martin Peter Johnson was born in 1858, in Sköttning, Västra Götaland, Sweden. Trained as a carpenter, Martin and his sister were the first in their family to emigrate to Minnesota. He married Sophia Hegg in 1891 and the following year, moved to Grant County and established their homestead.

Martin and Sophy had 13 children in 24 years. When he died in 1913, at the age of 55, his oldest son, Arthur, was 20 and assumed management of the family farm.

It’s hard to imagine what a farmer of the early 20th century would make of a 21st-century farm. In 1915, the year Arthur married, the point of a Minnesota farm was, fundamentally, survival. Jay says, “I remember my dad painting the picture that you survived the winter. That was the goal, just to get through the winter.” With that in mind, farms featured livestock for food, dairy, wool, and work; and the crops to feed those animals. Cattle, horses, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens and ducks lived on corn, oats and alfalfa, plus the farm grew wheat for straw and to sell. Fieldwork was done by horses or horse-powered threshing machines. And a trip to town or a visit to friends was done on horseback or in a buggy. But the drawback to such an animal-intensive operation was the need to be hands-on, 24/7/365. No vacations with all that livestock to feed. All in all, the farmer of the early 1900s had to be a botanist, a meteorologist, a veterinarian, a carpenter, a mechanic, a geologist, an economist – and a gambler.

In the years that Arthur farmed in Grant County, his operation changed. The only animals left on the farm by the mid-1970s were some chickens and the steers he raised to sell. His land was in corn and alfalfa to feed the cattle, and some small grains: wheat, oats, and barley.

Arthur’s oldest son, Merl, farmed with his father and took over the operation after a stroke in the late 1970s put an end to Arthur’s farming days. Arthur had no choice but to take over when Martin died, but Jay doesn’t think his dad had much of a say-so either. “He never had a choice – (farming) was what he’d learned and what he knew. He farmed with his dad from the get-go and never needed (or) had the desire to do anything different. (Doing something else) wasn’t something that he’d even thought of.”

Jay worked alongside his father and grandfather, then entered farming full-time after graduating from the University of Minnesota in 1980 with a degree in Agricultural Economics.

“Now what we raise is worth something in the world marketplace”

When the Russian Grain Embargo was signed into law by then-President Jimmy Carter in January 1980, over 100 years of farming changed, too.

“The whole industry changed overnight,” Jay said. “Agriculture went from ‘you raise crops for your own use to feed your cattle to survive as a family’ to ‘this is an industry.’ And now what we raise is a commodity that is worth something in the world marketplace, not just the local state or county. The world was going to beat a path to my door if I was farming. Prices were really good, and all farmers were going to be wealthy …“ Here he stops and grins. “So it was a pretty easy choice for me to go into agriculture.

“But then the ‘80s came. And then all of these guys that borrowed money and expanded their business were filing bankruptcy. The prices of land went down. I remember going to my dad and saying ‘We should buy this farm’ you know – get bigger, get bigger. And he sat there with his feet up in the recliner, ‘No, we’re not doing that.’ He always said, ‘This farming big – it’s overrated. Take care of your family. Live within your means.’ So there was the contrast between Art and my dad; I think Art was a tycoon. Lots of cattle; he’d buy land and sell it to other farmers – kind of a wheeler and dealer. But Merl wasn’t.”

When farms were small, sustainable operations to feed a family, it also meant farmers were needed on the premises, hands on, 24/7/365, because animals needed to be fed, watered and cared for. Arthur and his wife, Jensine, were tied to the farm full-time, even when the only livestock on the place were the feedlot cattle. So Arthur only left the county of his birth once a year – to take cattle to the South St. Paul stockyards.

Once the cattle were gone, Merl maintained (to Arthur’s disgust) a yearly trip to visit his Army buddies in various places around the country. “Disgust” because a single-minded focus on work was not just a survival tactic, it became part of the family culture.

“I remember talking to my dad and saying, ‘Dad, I’ll never be able to work as hard as you,’ recalls Jay. “Because he always worked. I remember that one time we’d gotten the machinery ready, we were all done with everything, everything was caught up – there was nothing to do! He says we’re gonna go in the woods and clean up branches that had fallen in the woods. I could not believe it. He could not help himself! Now that I tell the story I can’t remember; was that the same time or another time he told me, as hard as he worked he would never be able to work as hard as his dad.” Jay, a singer and musician, worked plenty hard himself. But he and his wife, Betty, childhood sweethearts who married while still in college, made it a point to balance the hard work of farming with music, ski trips, and travel whenever they could. The couple even headed up a family band.

The 1990s

Thanks to hard work and wise counsel, the Johnson farming operation survived the 1980s. But in the ‘90s, Jay said it was even harder than the ‘80s and he almost gave up many times.

In 1991, his parents moved off the farm and into town, and a few years later, Jay’s family moved into and started renovating his childhood home.

“I remember ‘92, ‘93, ‘94 – didn’t make a dime farming. It was break-even, at best. I seriously entertained looking for a job in the Cities and moving,” he says. “Because the burden of ‘you’ve got to get bigger or go home.’ To stay the same is to get smaller. And then it’s not as profitable.” Jay also worked winters for the government, appraising property. “The USDA had a branch at the time that financed farmers. I went there and I said ‘I can work from November through March; middle of April I gotta go farm’ and they said, “Do you want to work in Alex or Fergus?’”

“And then ‘99 came and the price of corn went to $7.00, so I went “Ok! I’ll stay here!” Pendulum swinging the other way! ‘99 was a huge turnaround year.”

The (really) empty nest

Martin Johnson’s great-great-grandchildren might not be farming, but Jay and Betty’s three kids are far from slackers.

Their daughter Leah is a chemical engineer at Medtronic, with a newly-minted MBA in Business Administration; daughter Leslie is a chemical analyst with Kindeva Drug Delivery (a spin-off of 3M) and works developing drug delivery systems; and son Mitchell is an aerospace engineer at Boeing, with a masters in aerospace engineering and working primarily with wind tunnel and wind shear tests.

And while the couple didn’t actually sit down and say “We’re the last generation of farmers,” they started to see the writing on the wall.

“I think when they all went off to college we kind of had a clue,” says Betty. “Sometimes people go off to college and come back once they’ve spread their wings. And there’s a bunch that have come back here after working in the engineering field or something; they decide to come back and farm.”

Interestingly, among their similar-aged friends, Jay can’t think of any instances were daughters have taken over the farming operation, just sons. Although daughters have gotten involved when they married other farmers.

“If the girls would have shown any interest at all, I probably would have encouraged them,” says Jay. “But they didn’t, so I didn’t encourage them – now what comes first, the chicken or the egg? Should I have encouraged them and said, ‘Look, you can do this, too’ ? Did I say the wrong thing at the wrong times? Should I have done more to encourage them or cultivate a passion for farming in my girls? I don’t know.”

What comes next

So now, as they’re contemplating the start of their own retirement, Jay and Betty, like farmers all around Minnesota, are coming to terms with the farming tradition their immigrant great-grandparents brought and reestablished here and what being the last generation to farm this land means. For Jay, it’s a combination of relief and disappointment.

“It’s a dichotomy. I’m probably more of a dreamer. One of the characteristics of my personality is the focus on that legacy part of it and the romance of having the son take over. From a business standpoint that doesn’t make any sense. I was relieved that Mitchell wasn’t going to farm and then disappointed that this was going to end. Art, Merl, Jay … and now nobody.”

Don’t get them wrong: if one of the kids had wanted to stay and farm, Jay and Betty would have supported them 100%. But there is a silver lining to the way things worked out. “That was one of the reasons you were relieved that Mitchell wasn’t farming,” Betty laughs over at her husband. “Jay would have still been farming until he was 80. Our friends that have kids that have taken over the farm; they are still having to work – they can’t retire. Their kids need the extra help that isn’t a paid employee!”

For now, they’re maintaining a life that includes their Grant County farm, their Twin Cities condo, and plenty of grandkid time in Seattle and Minneapolis. That stands another longstanding family tradition on its head: where children always travel to see the parents but never vice versa. To Jay and Betty, if they have the time and ability to travel, it just makes sense. It’s not unusual for Betty to hop on a plane and head to Washington state to fill in when her son and daughter-in-law don’t have daycare, but for the next four years, they plan to leave a lot of options open.

Betty says, “I guess, to us, what we’d like to do is be close to the kids and grandkids. But there’s no guarantee that they will stay where they are. I really like our place in the Cities; the fact that we can turn the key in the lock and we don’t have to worry about it at all. Whereas this place…” Her gesture encompasses their comfortable farmhouse with its huge kitchen, music room, and big windows everywhere looking out on huge old trees and miles of farmland. “A lot of worries and a lot of things to go wrong.”

The Johnsons – Jay and Betty and various combinations of kids and grandkids – love to travel, learn new languages, ski and bicycle. Jay is still singing with various music groups in the Cities and up north, and the family recently returned from a trip to Norway where they visited the Flatness farm, also part of extended family and the farming tradition. Arthur’s wife, Jensine Flatness’s people, immigrated from Norway around the turn of the century.

They’re giving themselves four more years to explore options, then, having watched the previous generations navigating (or not) life after farming, they’ll start making some decisions. The key is to move before you’re forced to, says Jay. Make a decision where you want to be and go there. Then, while it’s still do-able, meet people and forge new relationships.

As for the farm, eventually the land might be broken up and sold, but if it is, it won’t be on Jay Johnson’s watch. He thinks about (and watched first-hand ) the work of the previous generations to tend the land, make it provide for their families and then the world, sustain a business. He has albums of photographs of this place and its people, where so many grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were born, raised and even married. “What am I gonna do? Sell it?” Jay can’t even contemplate it. Even if his name is the last Johnson in a line of Johnsons on the paperwork, he thinks of Martin and Arthur and Merl and says, “It’s not mine to sell.”